Energy Security Current Issue

Dragon at Detroit’s gate

The Chinese debut at the Detroit Auto Show with Geely, a mid-sized sedan planned for sale to budget-conscious American families for less than $10,000 by 2008, should be viewed as the opening shot in what is likely to be a clash of titans between the American and Chinese auto industries, one that could send Detroit to the ropes. IAGS Co-director Gal Luft analyzes the implications.

Wrestling the Russian Bear

Russia's curtailing deliveries of natural gas to Ukraine goes far beyond the bounds of a common commercial dispute between an energy supplying and an energy consuming nation. It is indicative of Russia's foreign policy vis-à-vis the Soviet Union's former allies spread across Central and Eastern Europe not to mention a warning shot across the bow of Central Asian energy exporters. IAGS Senior Fellow Dr. Kevin Rosner outlines necessary steps to neutralizing Russia's energy weapon.

Sino-Japanese oil rivalry spills into Africa

China and Japan - the two giants of East Asia - are competing for energy

resources around the globe. Their rivalry in the East China Sea, Russia,

Central Asia and Southeast Asia has been well documented. Yet little has

been written in Washington about the impact of Sino-Japanese rivalry in

Africa.

With one-third of its top 15 oil suppliers in Africa, the United States

ignores the challenges of this geopolitical dynamic at its peril. Joshua Eisenman and Devin T Stewart discuss.

China deals a blow to India's aspirations in Kazakhstan

The "unconditional" final ruling of October 26 2005 by the Alberta Court of Queen's Bench, Canada, in favour of China's China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC) dealt a severe blow to the last Indian hope of acquiring PetroKazakhstan. The defeat in securing an important energy deal does not bode well for India's energy security concerns considering its growing energy needs and illustrates India's vulnerability in competing and securing depleting international energy sources. At the same time it opens up for greater debate the Indian energy minister's fervent argument that Asia's two emerging economic giants should co-operate rather than compete in securing international energy deals.

Oil puts Iran out of reach

As diplomatic rumbles regarding sanctions against Iran fill the airwaves, IAGS' Gal Luft notes that given Iran's key position as an oil supplier and the tightness of the oil market, Iran's influence on the world's economy makes it virtually untouchable.

No doubt, Iran is heavily dependent on petrodollars and denying it oil revenues would no doubt hurt its economy and might even spark social discontent. Oil revenues constitute over 80 percent of its total export earnings and 50 percent of its gross domestic product.

But the Iranians know that oil is their insurance policy and that the best way to forestall U.S. efforts in the United Nations is by getting into bed with energy hungry powers such as Japan and the two fastest growing energy consumers, China and India.

Threatening Iran with sanctions may well force it to flex its muscles by cutting its oil production and driving oil prices to new highs in order to remind the world how harmful such a policy could be.

On the technology front

How utilities can save America from its oil addiction

Utility companies which have traditionally viewed themselves as providers of "power" for lighting homes or powering computers, can now break the dominance of Big Oil in the transportation energy sector and introduce much needed competition in the

transportation fuel market. Gal Luft explains how.

Comparing Hydrogen and Electricity for Transmission, Storage and Transportation

Study: Coal based methanol is cheapest fuel for fuel cells

A recently completed study by University of Florida researchers for the Georgetown University fuel

cell program assessed the the future overall costs of various fuel options for fuel

cell vehicles. The primary fuel options analyzed by the study were hydrogen from natural gas, hydrogen from coal, and methanol from

coal. The study concluded that methanol from coal was the cheapest option, by a factor of almost 50%.

Major improvement in fuel economy and range of Honda's fuel cell vehicles

The 2005 model Honda fuel cell vehicle achieves a nearly 20 percent improvement in its EPA fuel

economy rating and a 33 percent gain in peak power (107 hp vs. 80 hp) compared to the 2004

model, and feature a number of important technological achievements on the road to commercialization of fuel cell vehicles.

Biodiesel fueled ships to cruise in Canada

A Canadian project will test the use of pure biodiesel (B100) as a fuel supply on a fleet of 12 boats of various types and sizes,

11 boats on pure biodiesel (B100) and one on a 5-percent blend (B5).

IAGS is a publicly supported, nonprofit organization under section 501(c)3 of the Internal

Revenue Code.

IAGS is not

beholden to any industry or political group. We depend on you for

support. If you think what we are doing is worthwhile, please Support

IAGS. All contributions are tax deductible to the full extent allowed by law.

Property of The Institute for

the Analysis of Global Security © 2003-2006. All rights reserved.

Back Issues

|

Sino-Japanese competition for Russia's far east oil pipeline project

Introduction

There are two significant energy trends underlying the competition between China and Japan for Russia's Far East oil pipeline project: the need to seek additional energy supplies and to pursue greater energy diversification. And for both China and Japan, Russian energy offers a significant additional supply source and contributes to greater diversification. But these trends in energy interests are matched by an equally dynamic and intense geopolitical rivalry, defined by a complex and contradictory set of converging and diverging national interests.

Within this context, the competition between China and Japan, as well as the Russian role in exploiting this rivalry, is driven by the distinct energy interests of each country:

China's position is largely defined by the demands inherent in its fairly recent rise to replace Japan as the world's second largest oil importer, with internal demands driven by rising consumption and serious inefficiency;

Japan's position is also driven by the challenges imposed from its own energy insecurity, its worsening relations with China, and from a still weak relationship with Russia; and,

In the short- to medium-term, Russia's position is dominated by its position as the world's second largest oil producer, and magnified by its over-dependence on energy revenue.

Pipeline Courtship

The Chinese-Japanese competition for securing the role of primary partner for Russian energy exports from the Far East is much less a commercial competition than a complex courtship. The usual economic considerations inherent in a strictly commercial competition do not apply in this case. Instead, as in the case of the earlier Baku-Ceyhan oil pipeline project, geopolitical considerations far outweigh any and all commercial considerations. Moreover, in the case of the Russian Far East oil pipeline project, the standard determinants of pipeline cost, length and capacity, are demoted to secondary considerations.

The Japanese Route: Angarsk-Nakhodka

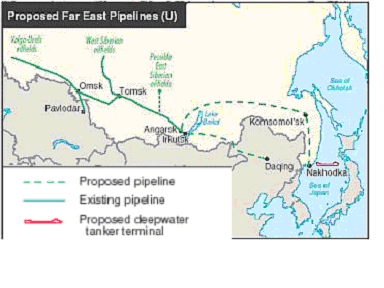

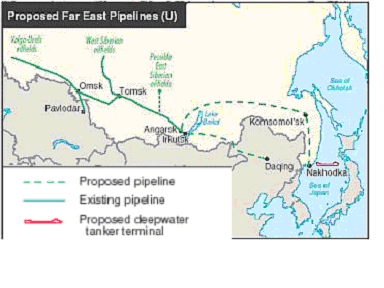

The Japanese route, from Angarsk to Nakhodka, would be roughly double the price and, at a projected 3700 km, would be significantly longer than the Chinese alternative (see map below).

The Significance for Japan

For Tokyo, the Angarsk-Nakhodka pipeline is most significant for two strategic reasons. First, the pipeline could result in an estimated 10-15 percent reduction in Japan's reliance on Middle Eastern oil imports. This reduction alone would offer an important new element of import diversification and, within the new landscape of international security, perhaps even spark a move away from imports from the volatile Middle East.

A second strategic factor for Japan stems from the fact that if Tokyo is able to conclude a successful agreement with Russia, it would represent a strategic reengagement with Moscow. Such a reengagement would be an important correction to the marked decline in Japanese economic and political influence, and even presence, in Russia through much of the late 1980s and into the early- to mid-1990s.1

This decline in Japan's position with Russia has been especially damaging over the longer term, as China was able to rapidly assert and deepen its relationship with Russia at the expense of Japan. Therefore, such a reengagement would help to match or even offset the recent gains in China's geopolitical pursuit of greater proximity to Russia (and Central Asia).

The Outlook for Japan

The most fundamental obstacle to the Japanese route is neither one of economics nor energy. As seen in the nature of the pipeline competition itself, the main obstacle for Japan is geopolitical. Specifically, the main challenge for Japan stems from its territorial dispute with Russia over the Kurile Islands.2 For Japan, the challenges of dealing with its wartime record continue to impede and impair its relations with its neighbors. And the territorial dispute with Russia, despite attempts of diplomatic diversion, is a both a problem of the past and of the present. It is a problem of the past, being rooted in history, and it is a problem of the present, as it remains an unresolved issue. But it is also a problem of the future, as it is remains an impediment to the course of Japanese relations with an important regional power.

The Chinese Route: Angarsk-Daqing

The Chinese route, running from Angarsk to China's energy-rich region of Daqing, would be considerably shorter, at 2400-km, and significantly cheaper. This route also conforms to the changing nature of the Russian Far East. Specifically, the Chinese link follows a pattern in the Russian Far East of increasing integration into what can be defined as a "greater Chinese economic space."

This trend of integration also fuels the Russian fear of Chinese penetration into the Russian Far East, exacerbated by Russia's demographic vulnerabilities and by the remote and poor state of the region's infrastructure. This fear was also a significant factor in Russian President Putin's determination to restore central authority and control over the Far Eastern governors in an attempt to reverse their relative autonomy garnered during the Yeltsin years. 3

The Outlook for China

For China, one of the more basic challenges is Russian reluctance, hesitation and delay. This stems from the limited nature of the Chinese option, as with the case of Russia's "Blue Stream" natural gas project with Turkey, there is a significant Russian reluctance for projects with only one "end-user." But in the reality of the global energy market, this fear may be essentially more political than practical. 4 It is also apparent that the Russian strategy is one of delay, and as this pipeline courtship continues to drag on, Moscow can be expected to hold out for as long as possible before selecting a final partner. The danger for Russia is that it may delay for too long and overplay its hand by overestimating its position, mirroring an overall pattern of Russian immaturity.

The most interesting factor in assessing the outlook for the Chinese pipeline route is demonstrated by the shifting dynamics of geopolitics. Generally, the altered geopolitical landscape in Eurasia, and more specifically, the fact that the United States can now be defined as a Central Asian power, may serve as an overriding strategic consideration for both Russia and China. In some ways, it is this Central Asian consideration that is also helping to drive Russia and China into a closer working relationship. This tactical realignment is further driven by a shared perception of an assertive U.S. agenda seeking to diminish or challenge Russian and Chinese interests in the region.

But for China, there is a danger that this convergence of strategic interests may induce Russia to seize an opportunity for greater leverage, perhaps gambling that China's overriding interest in securing Russian assistance in countering the U.S. presence in Central Asia may include a Chinese willingness to sacrifice the Far East energy deal. In this light, Russia could see a chance to maximize its position by leveraging its energy position from a zero-sum game into a win-win gain.

The Strategic Imperatives of the Pipeline Courtship

As argued earlier, the core determinant of the Chinese-Japanese pipeline courtship of the Russian Far East is only one element in a deeper geopolitical contest driven by the differing strategic imperatives of each country. Therefore, in order to present a more complete assessment, it is necessary to examine the essential nature of Chinese, Japanese and Russian interests.

China's Energy Imperative

Most traditional assessments of China's energy strategy miss a fundamental point and start from a mistaken premise. Specifically, unlike far too many analyses warning of the rise of China, China's energy policies are actually rooted in weakness and worry. The weakness is demonstrated by a serious imbalance between the location of its energy resources and its main centers of energy demand, and reflected in the overwhelming vulnerability of China's access to external energy supplies.5 This inherent weakness defines the Chinese energy strategy and, most importantly, results in two distinct needs: for greater energy imports and for a modern infrastructure able to span great distances.

China is also beset by worry over the challenge of managing its mounting energy demand. It is readily accepted that the sharp rise in Chinese demand for energy is a priority for Beijing. And with a rate of increase surpassing global demand by some four-to-five times, China's demand for ever-increasing energy is an obvious concern.6

There is another aspect of the importance of meeting its rising energy demand. Although it is a fairly simple assertion that adequate energy supplies are essential for continued economic growth, there is a corollary political consideration. This is demonstrated by the reliance of the Chinese state on economic growth for political stability and regime legitimacy. In this way, any threat to the delicate relationship between secure energy supplies and sustained economic growth is a threat to the legitimacy and security of the Chinese state. Thus, China's energy policy is one of political legitimacy as much as economic growth. And it is through this prism that one can best understand the Chinese view of energy as a strategic imperative.

The outlook for Chinese energy policy follows a trajectory marked by two significant external factors. First, Chinese energy strategy is no longer a regional approach. Its parameters have expanded into an international context, with China's pursuit of energy resources surpassing geographic boundaries and ideological barriers. This expanded scale and scope of Chinese energy strategy is expressed on three levels. One level comprises regions and areas of U.S. "benign neglect," such as Canada and South America. These areas can be seen as new considerations for Chinese energy planners, as there is a perceived vacuum in the wake of American "benign neglect."

Another level of this new Chinese energy engagement is comprised of the energy-rich "pariah states," or member states of the so-called "axis of evil." These "pariah states" include countries such as Iran, Sudan, and Angola that remain closed to investment or exploration by Western energy firms. For these states, China's engagement is virtually unopposed. The third and final level of engagement is a combination of the first two, and is demonstrated by the case of Venezuela, where China is warmly welcomed.

The second defining factor in the new trajectory of Chinese energy policy is one of potential conflict with the United States. This potential conflict between China and the U.S. for position in global energy will not be a direct confrontation, however, but one marked by a competition for secondary markets and suppliers. 7 Such an indirect confrontation will most likely center on areas of U.S. absence or neglect, fostering a new arena for Chinese-U.S. rivalry and jockeying. Central Asia can also be viewed as one of the more prominent of these new arenas.

This new Chinese trajectory is moderated by two important internal factors. First, Chinese energy strategy is still mainly defensive, rooted in the Chinese strategic fear that the U.S. will seek to block or contain its pursuit of energy resources in an attempt to weaken or destabilize the Chinese state.8 Second, the course toward energy-driven confrontation with the United States is offset by a convergence of interests. These shared interests are intricate and intertwined, as in terms of regional security, such as in the North Korean case, and even in energy interests, as with the common need for the security of sea lanes. For China, the shared interest in maritime security is a priority and is only compounded by the Chinese vulnerability regarding the Strait of Malacca, which accounts for the passage of four-fifths of Chinese oil imports.9 Thus, although China's energy strategy is increasingly active and assertive, it remains offset by an inherently defensive approach that will avoid direct confrontation with the United States at all cost. Hopefully, the convergence of Chinese and American security interests in the Asia-Pacific will soothe the signs of indirect competition in the emerging arenas of Latin America, Africa, and Central Asia.

Japan's Transformation

As with China, there is a deeper set of driving forces determining Japanese energy strategy. After a series of prolonged economic difficulties and political paralysis, Japan is now undergoing a profound transformation. In some ways, the impetus for Japan's transformation has been a result of accumulating tension, insecurity and a mounting pressure for change. This has fostered a degree of readjustment, mainly through a traditionally Japanese approach of gradual, evolutionary change designed to limit any unsettling or destabilizing effects on the Japanese society and system.

These changes have followed a gradual course of reevaluation, but have included a serious reexamination and questioning of Japan's very identity and future. Within this course of reevaluation, there have been three specific changes that comprise Japan's overall transformation and that exert influence over both the Japanese approach to its competition with China and its developing relationship with Russia. The first change has been a reexamination of Japan's international position and influence. This has been demonstrated by the Japanese deployment of peacekeeping troops to Iraq and its bid for a seat on the United Nations Security Council.

The second element of this Japanese transformation was its expanding regional role as a U.S. proxy force and more active ally in the Asia-Pacific region. This expanded role can be seen in Japan's participation in the U.S. plan for theater missile defense and is also evident in the steady modernization of the Japanese Self-Defense Forces. Further, the expanded area of operations and extended deployment of Japanese forces in support of the U.S.-led "war on terror" represents another important aspect of this enhanced regional role.

And finally, the Japanese recognition of its regional power and influence as both a necessary and positive objective marks the third element in the country's transformation. Such recognition has been bolstered by Japan's threat environment, with greater concern over the buildup of the Chinese military and from the perception of threat posed by North Korea. Japan's emphasis on its military has been without any stress on militancy. Thus, each of these aspects of Japan's transformation has contributed to its competition with China for Russian energy as part of a broader dynamic. And although the emergence of a vibrant and heated Chinese nationalism has exhibited strident anti-Japanese feeling, it has been the continued dispute over natural gas reserves in the East China Sea that has most recently fueled this Japanese-Chinese rivalry.

Russia's Energy Strategy

The Russian role as an arena for competition between China and Japan stems as much from Russian energy strategy as from the Chinese-Japanese geopolitical rivalry. Under Russian President Putin, energy has emerged as a tool for strategic leverage, in effect replacing the traditional Russian reliance on the "hard power" of its military with a new exercise in Russia's "soft power."

This use of energy as leverage consists of three components. First, it has supplemented, and in some cases even projected, an effective reassertion of Russian power and influence within the so-called "Near Abroad" of former Soviet states. Most notably, this can be seen in the Russian dominance over the energy sectors of much of the South Caucasus and Central Asia. Second, it has also featured the use of energy as a tool for strengthening state power, empowering Russia's status as a regional and, in this case, as an Asian power. And thirdly, it has offered Moscow an attractive way to restore its international position and regain its geopolitical relevance.

But in the case of the Chinese-Japanese competition for the Russian Far East, it has also revealed Russia's fundamental weakness. Despite the tactical gains from the use of energy as leverage, Russia's energy sector remains beset by four serious shortcomings: it has no unutilized capacity, its oil is relatively expensive to produce, it has a limited pipeline capacity, and is still not yet a global energy player. Therefore, Russian energy strategy is predominantly driven by weakness and need.

There is also a broader strategic dimension to Russian energy strategy, however. The Russian strategic perspective views energy as an integral part of an overall projection of Russia power and position. It is energy that most clearly marks a Russian shift toward Asia and away from Europe. And as an aspiring Asian power, Russia sees no real threat or challenge from Japan (other than the unresolved territorial dispute). But it views China more as a rival power, and despite its rather reluctant partnership with Beijing, Moscow is consumed by a fear of Chinese expansion and penetration into the vulnerable Far East.

Conclusion

Given the long duration and delay of the Far Eastern oil pipeline project, there can be no real conclusion at this time, as the competition remains dynamic and unresolved. Instead, there are five key assessments that can be derived from this case. First, energy competition has emerged as only one aspect of a broader geopolitical contest heightened by a potential clash or conflict of competing interests. Second, the looming energy competition between China and the United States actually serves to frame a broader framework for this pipeline courtship, most likely to emerge in new arenas, such as the regions and areas of U.S. neglect or absence, mainly in South America and Africa, and over "pariah" states, like Iran and even Venezuela. This competition will feature a new intensity but will most likely be contained to a series of indirect clashes, as China will undoubtedly avoid any frontal or direct confrontation with the United States.

Third, Chinese-Russian relations, including energy ties, are on a path of converging interests, partnering in response to the U.S. military presence along their borders and reacting to recent U.S. policies emphasizing democracy promotion and regime change. In fact, this is the underlying motivation for the close Chinese and Russian approach to the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), spurring and solidifying bilateral military ties, and for a greater coordinated response to the "revolutions of fruits and flowers" in Central Asia and other former Soviet states. Both Beijing and Moscow hold a starkly different interpretation of the recent "revolutions" in Georgia, Ukraine and Kyrgyzstan, than Washington. Moscow sees them not as democratic victories of people power, but as externally-financed assaults on its traditional and even natural spheres of influence. And Beijing sees these developments as part of a broader American strategy of encirclement, aimed at curtailing China's expanding economic, political and energy ties.

Unlike the first three assessments, however, the case of competition for the Russian Far East also reveals some positive and encouraging trends. The fourth assessment demonstrates that despite the elements of competition and contest, energy is also an important area of potential stability and security. This is most evident in two cases: the still developing U.S.-Russian strategic partnership, with the promise of Russia as America's "energy ally," and by the shared interests of energy security common to both China and the United States.

Finally, the last assessment is based on a contention that the converging energy interests of these powers can be greatly enhanced and bolstered by the precedent of region-based cooperation. The recent example of the six-party talks as a region-based, coordinated effort to address the North Korea issue offers an important confirmation of the need for multilateral security in the Asia-Pacific region. And with such a demonstrated foundation of shared interests, the security outlook for the Asia-Pacific reflects more promise than peril. But the outstanding questions are whether this region-based approach will last, or if the Asia-Pacific will revert to the division and competition of these powers' unilateral impulses and energy imperatives.

Richard Giragosian is an IAGS Research Associate.

1 Bogaturov, Alexei, "Russia's Priorities in Northeast Asia: Putin's First Four Years," Brookings Northeast Asia Survey 2003-04, The Brookings Institution.

2

For more on the tenacity of this territorial dispute, see Professor Peter Rutland's insightful analyses, in "Distant Neighbors," Russia and Eurasia Review, The Jamestown Foundation, Volume 2 Issue 2, January 21, 2003; and "Russo-Japanese Relations Improving," Russia and Eurasia Review, The Jamestown Foundation, Volume 1 Issue 57, July 22, 2004.

3

Bogaturov.

4

According to FACTS Inc. Senior Consultant Tomoko Hosoe, "…at the end of the day, if oil flows to Nakhodka it will find a buyer- crude is a liquid market and the price, of course, will be competitive." Email correspondence with author.

5

Andrews-Speed, Philip, "China's Energy Woes: Running on Empty," Far Eastern Economic Review, Vol. 168 No. 6, June 2005.

6

Ibid.

7

Zweig, David and Bi Jianhai, "China's Global Hunt for Energy," Foreign Affairs, Volume 84 Number 5, September/October 2005.

8

Ibid.

9

Ibid.

Top

|

Energy Security

Prepared by the Institute for the Analysis of Global

Security

Energy Security

Prepared by the Institute for the Analysis of Global

Security